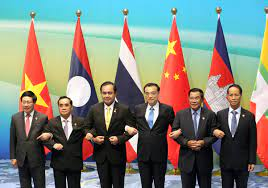

Migrant laborers worry that Thailand may remove Cambodian and Laotian workers.

After the May 22 military coup, Thailand expelled 200,000 Cambodian laborers in June 2014. Adhoc branded Cambodia’s expulsion procedures “uncivilized and inhumane.”

Nationalist policies damaged both economies.

Despite appearing to damage solely Cambodians, such a strategy would cut off the Thai economy’s arms. As their economy becomes more skill-based and less labor-intensive, Cambodian, Laotian, and Myanmar employees are undertaking menial occupations Thais no longer desire.

Thai politicians should recognize and appreciate these employees, without whom Thai people could not live better and prosper. Instead of fueling economic nationalism for political support, they should appreciate those who sustain their livelihoods and economies.

Remember the Cebu Declaration and ASEAN Consensus on Migrant Workers’ Rights.

These acknowledged the shared and balanced obligations of ASEAN’s receiving and sending governments to support migrant workers and their families’ full potential, dignity, basic rights, and fair treatment.

Responsible leaders in the Mekong Region should avoid policies that may harm locals. Separate politics and economy.

Inciting military mutiny and insurrection to overthrow the government is Sam Rainsy’s political hallmark.

His anti-China and Vietnam rhetoric is well-known. His group’s lobbying to get the EU and US to revoke Cambodia’s Everything But Arms (EBA) and Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) special status is most worrying. They want foreign politicians to impose economic conditions to influence Cambodian politics.

The apparel industry should be most affected. But losing over 800,000 workers in this industry, mostly women, to gain political leverage by undermining the economy and removing government support would be like burning the house to cook an egg.

After being exiled, Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra never advocated for other countries to punish Thailand’s economy.

Aung San Suu Kyi never called on foreign countries to harm Myanmar’s economy, even when imprisoned and determined to overthrow the military dictatorship.

Cambodian politicians can behave even worse.

Even though China and Vietnam usually appear like they’ll fight a war tomorrow over the South China Sea conflicts, their officials have seldom sought to destroy their strong economic links.

Last year, Vietnam-China commerce reached US$234.9 billion, up from $106.71 billion four years earlier. China’s sixth-largest commercial partner worldwide is Vietnam.

China and Vietnam have deepened their commercial links, thinking that economic and people-to-people linkages may protect peace from unanticipated conflicts.

Politicians in the Mekong Region must ethically separate economy and politics.

No matter how fierce their political fights, they should never ask other nations to impose economic penalties on them. Internationally, despite their political disagreements across the border, leaders should not jeopardize the lives and well-being of the region’s interdependent people.

Politicians must foster peace, stability, goodwill, and shared prosperity.