Last week, former president—and 2024 presidential candidate—Donald Trump threatened to “fire” college accreditors. He claims accreditors have failed to safeguard students from “Marxist maniacs and lunatics” who have taken over higher education.

Many of the nation’s accrediting agencies are used to staying out of the political limelight, but DEI projects and critical race theory may surprise them. For more than two years, politicians have accused the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools of ideological influence and “wokeness”—some of whom have filed legislation to restrict its authority in their states.

Longtime SACS president Belle Wheelan said the attacks have grown as the culture wars have dominated the national debate surrounding higher ed and ambitious players like Florida governor Ron DeSantis seek to turn universities into political cudgels.

Legislation has always affected higher education. She stated academic freedom was rarely interfered with.

“Things are different and more invasive.”

SACS was one of seven key regional accreditors until recently. The Trump administration allowed accreditors to monitor universities nationwide in 2019, making them all “national” bodies.

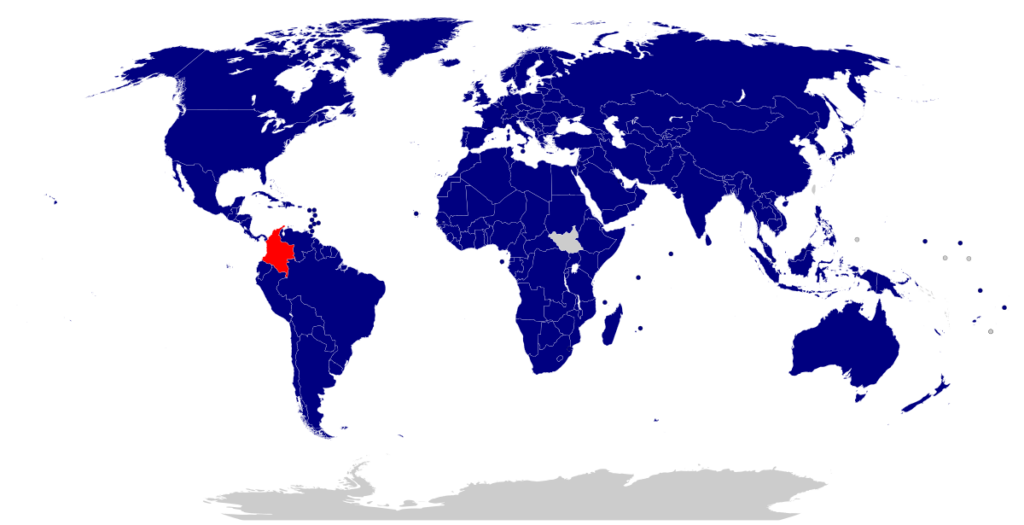

The seven regionals function mostly in their historic districts. Texas, Tennessee, and Florida are among SACS’s 11 conservative states.

Trump’s criticisms on accreditors last week resembled those of his potential 2024 Republican competitor, DeSantis, with whom SACS has a particularly tense relationship. The accreditor has warned the governor about his unusual measures, including changing most of the New College of Florida board, and DeSantis is fighting the accrediting “cartel.”

If the law passes, most of Florida’s colleges and universities will have to find a new accreditor because SACS is still the principal one.

Texas and North Carolina lawmakers have introduced similar bills to challenge the major accreditors.

Former New England Commission of Higher Education president Barbara Brittingham said lawmakers don’t appear to understand the repercussions of forcing accreditation switching, and she doubts schools will do so on their own.

“Many people discussing accreditation right now don’t understand it… “Many of them are just caught up in the political theater,” she remarked. “If an institution wants to switch accreditors, fine… but if they’re forced to switch, that’s not only kind of a terrible ultimatum—it’s inefficient and expensive for the institution.”

Patient 0

Wheelan said she “has no idea” why Florida politicians led the SACS demonization.

However, New America senior education adviser Edward Conroy believes it began in 2021 when the University of Florida prohibited three academics from testifying against the state in a case over voting rights restrictions. SACS investigated the university to see if political pressure influenced the decision.

SACS’s rigidity irritated many in the for-profit and online program administration industries before that, according to Inside Higher Ed sources. It has been criticized for its handling of for-profit and online programs, minority-serving colleges, and underperforming institutions.

All sources agreed that these previous few years were the first time bureaucratic back-room fighting became hot public discourse.

“Accreditors have historically only attracted wonky policy analysts like me,” Conroy remarked. State officials have used accreditors as foils to make a point. However, in the past two or three years, they’ve become political punching bags.

Some claim SACS caused this scrutiny. Adam Kissel, a visiting scholar at the Heritage Foundation and former assistant to Betsy DeVos, said the accreditor has shown a political bias in investigating institutional acts. He cited SACS’s practice of evaluating institutions in reaction to media headlines—including at the University of North Carolina in January over the board’s unilateral construction of a contentious new school—as proof of its ideological tilt.

He said Belle has told SACS will act on news that worries them and contact out or investigate. “Since most media coverage is left-wing and she operates mostly in red states, it’s no surprise that this has taken on a political tone.”

Kissel also alleged the accreditor has often intervened in state lawmakers’ governance decisions to dismiss or elevate public institution executives and boards.

He said lawmakers have been preserving their right to governance in response to SACS’s targeting of institutions. Texas and North Carolina are thinking, “We need to get our institutions out from under SACS.”

Wheelan stated SACS’s Unsolicited Information Policy has been in existence since “at least 1999” and included examining media problems.

“We followed our policy,” Wheelan added. “I don’t know why the response has suddenly become ‘How dare you question what we’re doing?’.”

Leverage loss

When the Trump administration lifted accrediting limits in 2019, some projected an exodus of schools from the seven main accreditors, including SACS. Wheelan denied it.

“We only lost institutions through mergers or dropping them,” she added.

If the Florida law passes, others may follow. Mike Goldstein, managing director of Tyton Partners, a higher education and knowledge sector investment business, said that since Trump reduced restrictions, accreditors like SACS have had less leverage—for better or worse.

“This isn’t [Wheelan’s] first rodeo in Florida,” Goldstein added. SACS initiated an investigation after then-governor Rick Scott openly discussed removing the president of Florida A&M, an HBCU, in 2013. She had greater power then. Trump gave colleges additional options.”

“Belle knew the first time around she wouldn’t lose institutions,” he continued. “She can’t know this time.”

The Department of Education has cautioned that accrediting bills like Florida’s might lead to a loss of federal financial aid. Some policymakers and higher ed executives expect a retightening of accreditation rules this year, making it harder for schools in states that need it to locate a new accreditor.

“This year, we’ll have a whole regulatory process around accreditation,” Conroy added. I think some of the laws that were lifted under the Trump administration ought to be reinforced again to enable accreditors withstand political temptation to lower their standards.

Conroy warned the attention on accreditors might damage regulatory systems anyway. He concerns that SACS’s public trials may warn other major accreditors.

Accreditors face “challenging headwinds” from political attacks, he added. “SACS may have the hardest region for this problem, but other accreditors should also call out political interference and stick to their principles… They need to make sure they have all their ducks in a row and can back it up more and more.

Wheelan said she’ll hold SACS-accredited schools responsible in all her region’s states without penalizing them for politicians’ assaults or playing softball to get acceptance.

“Florida institutions are still mine,” she declared. “Until they’re no longer my institutions, we’ll treat them like all our other members.”

Miss Ball

Republican lawmakers have vented their SACS fury on Black Wheelan. Some politicians and right-wing higher ed consultants claim she has a history of obviously partisan intervention; her defenders say she’s a handy scapegoat for a reforming political movement that needs villains to legitimize itself.

Wheelan stated SACS is the only accreditor without a DEI requirement. “I’m not sure how I got to be the poster child for wokeness except that I am a woman and a minority.”

Even Wheelan’s detractors think Republicans are unfairly demonizing her for political gain.

Wheelan has clashed with Tyton Partners’ Goldstein. He stated his biggest concern with SACS is its unwavering dedication to a staid set of standards that he considers as constraining for new, creative higher ed businesses. Wheelan’s strong, top-down leadership style—not political influence—has precluded challenges to these standards.

Belle’s mistreated. “The ground beneath her feet has shifted, not her,” he added. “This naked politics is new.”

Brittingham, previously of NECHE, has known Wheelan for two decades and thinks the accusations against her are part of a political football game that might turn ugly.

“I feel for Belle,” she remarked. “The people pushing her want things in the political limelight, and she’s trying to stay out.”

Wheelan said the assaults are disheartening, but she remains faithful. She claimed it comforts her that most of her opponents “don’t understand how accreditation works” and don’t comprehend the various decision-making procedures that go into a reprimand or probe.

“I get the blame for all of this, but I get no vote,” she remarked. I accepted it 18 years ago. I understood.”